By Kenneth Osen

I have had a fascination with miniatures my entire life. My first important memories of them are from the Detroit Historical Museum when I was a child in the 1960s.

Walking through the museum with my parents, we came upon a new exhibit explaining a war with the Great Lakes tribes that occurred in 1763, known as Pontiac’s Rebellion. Part of the exhibit included wonderful shadow box dioramas depicting the events that occurred during that conflict, including a detailed interior of the British commander’s quarters.

I can still remember the step stool in front of the framed openings of the dioramas so little people like me would be able to peer into these miniature ‘time machines’. Like many children of my generation (I was born in 1956), miniatures and models seemed to be everywhere – museums, department stores, hobby shops, libraries – even grocery stores, and in my town, the local pharmacy. It was also my good fortune that my parents encouraged my interests, even making a work area for me in the basement. As a teenager my first full time job was at a large hobby shop in Detroit. There I met fellow modellers, some of whom became lifelong friends.

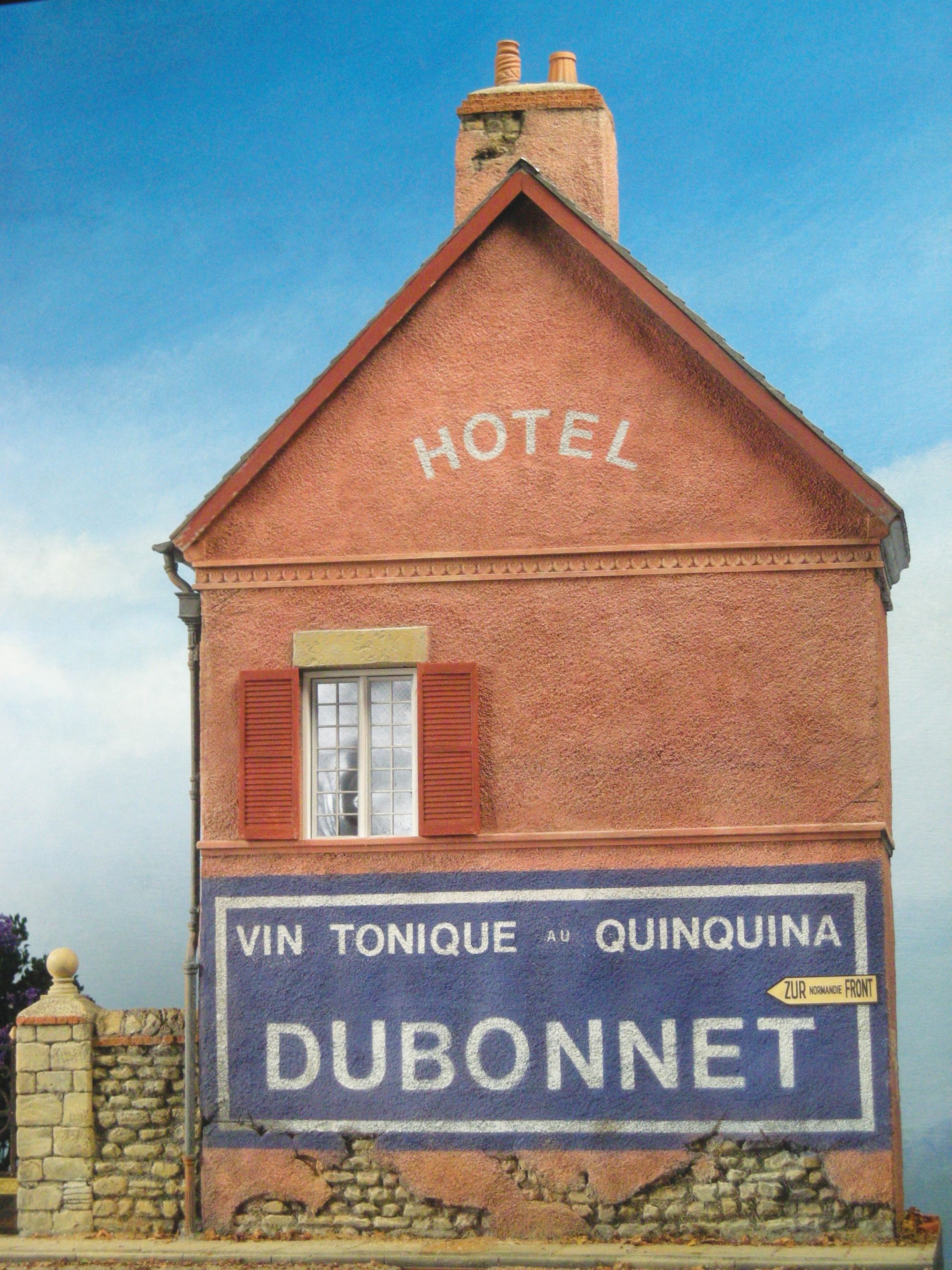

Even with college and other careers, I never stopped building miniatures. There were periods when one type got more attention than others. First were the military miniatures that my uncle had introduced to me, followed by aircraft and armour models. But my favourite throughout was model railways. It had everything – trains, buildings, people, scenery, and backdrops.

But just as important as the interest in miniatures was the deep love of history. With every new project, no matter the subject, I invested in research to get the details just right. Visits to museums, libraries, personal collections, and actual locations became a defining part of the hobby. Often the research prompted me to scratch build a piece or modify what was missing or wrong in a commercially available model.

A major turning point occurred in 1990 when I made a trip to Europe with a group of close friends to participate in a 175th anniversary event at Waterloo, Belgium. We had all made historic reproductions of British infantry uniforms from the 1815 period. Each detail was researched and handmade by members of the group.

We even learned the proper infantry drill and commands for that period of history. When we arrived, we became part of an army of over 5000 participants from around the world. Many of this group had become museum professionals, and, during one of our many discussions, they suggested that I should open a museum model studio. Less than a year later I did exactly that, specialising in historic models in various scales including full size mannequins dressed in historic reproduction clothing.

Remember those amazing dioramas I mentioned at the beginning of this article? Early on in my new career, I was working on an exhibit for the Detroit Historical Museum, that same place where I had first been so inspired by miniature representations of history. While looking for display cases and other items for a new exhibit, I found those same shadow box models in a storage facility. What a surprise!

They were long forgotten by the staff, and worse for wear, but the surviving details were still as exciting to see as they were when I was a boy. Even more interesting was an old cigar box laying on top of one of the cases. Inside was a stack of ‘in progress’ photos taken by the original maker during the construction of the models. It was riveting to see the models take shape with materials and techniques that I knew so well.

Each picture showed more progress, with the last few showing the finished results. I would guess that you could still smell the fresh paint when the last pictures were taken. When I placed the photos back into the box I knew that I had chosen the right path as a professional model maker.

Over 25 years later, I still enjoy the challenges of a new project. A new project might include a new time period or feature a subject that requires all new research, and a different scale might mean rethinking how the model should be built for a convincing or durable result.

When visitors stop by our studio, the conversation almost invariably turns to how something is made. I am always happy to talk about the process, and they are often surprised when I explain how it is done. These enthusiasts have made me realise that others might not know some of the methods that I routinely use which are so obvious and straightforward to me.

Some of these techniques can be tricky at first, but most of them, with a little practice and patience, are fairly easy to master. While newer technology can often yield fantastic results, traditional approaches, when well done, can be equally successful – and are often the better choice.